Deep fakes, fake news, it's old news!

The advances of AI and cheap compute power allow us to automate the making of “fake” media texts. Deepfake media generally points to media texts (e.g. audio, pictures and videos) portraying (celebrity) persona in events that have never taken place. The term deepfake references the use of deep learning to create the fake.

The interconnectedness of the internet allows us to disseminate media texts with unparalleled speed and depth into (social) networks. Articles with false information disseminate with the same ease. The term “fake news” points to any type of “news” article containing false information. Some are spread with the intent to disinform.

Don’t panic! Creating fakes and false information are not new. The spreading of false news as a (political) strategy has happened since at least the 13th century BC. Creating imitation pieces, like deepfakes, is probably equally old. The concept has been formulated as early as 100 BC.

The widespread availability of digital methods to create high quality (potentially large impact) “fakes” carry the same issues of any other type of fake. The problems of fakes are partly epistemological. It forces us to pose the uncomfortable questions: What can we actually know? What is true? How can we know something is true?

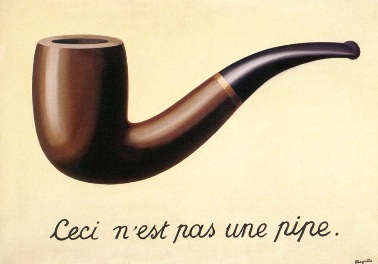

Surrealists (super realists) have played with these questions since the beginning of the 20th century. Just look at the picture painted by Magritte. It is a painting of a tobacco pipe. Pointing at it you’d say it’s a tobacco pipe. But is it? It’s not the tangible object of a pipe. And even knowing that it’s a painting of a tobacco pipe, the painting uses the reference to our mental representation of a pipe.

As far back as Plato (5-4th century BC) the question of what one can know was asked in relation to fakes. Plato’s allegory of the cave uses shadows as a concept of references to reality. It’s not surprising that in (cognitive) psychology it’s been found that the main model for humans to interpret the world, is by referencing mental representations of things in the world.

Having to rely on our own interpretation of the world, makes spotting fakes tricky. If your representations of the world are already slightly skewed, you might well interpret some fake news and deepfakes as real. Because of the fundamental interplay between fakes and our mental representations of reality, there is no easy solution to discern fakes. Experts and technology have never been a foolproof solution.

To study this issue further I recommend the video essay “F for Fake” by Orson Wells. Orson Wells layered it with all kinds of nuances between fake and real. In the end it's up to you to decide if something's fake. So which will you take? Red pill or blue pill?

Comments

Post a Comment